4 Cross sections and decay rates

To be able to compare our calculated amplitudes to experimental data, we need to a bit more work. We have (142)

| (230) |

The squared delta function is a problem because we only need one of them to solve our integration; the other delta function will then automatically lead to yet another . However, we have dealt with this problem before and know to write with the volume of spacetime . Therefore, we instead consider the probability per volume . We also need to keep in mind that the states require a normalisation . This leads to the probability density

| (231) |

4.1 Two initial states: cross section

Many particle physics experiments are scattering experiments where we take two particles and collide them. In analogy to classical scattering, we define the cross section of the scattering. Since we are working in a quantum theory rather than a classical one, the cross section describes a probability rather than a physical size.

Consider a cloud of particles of type at rest with number density . Now we shoot a bunch of particles of (a potentially different) type at the cloud (cf. Figure 3). Along the axis of collision, we have a cross-sectional area and bunch lengths and . The cross section of the scattering is defined through the number of scattering events as

| (232) |

Here we have also defined the total number of () particles (). The combination is called the luminosity and it is the reason that the cross section is a useful quantity. If we were to repeat our - scattering experiment at a different collider which has e.g. more particles in its beams, we would see more events even though the underlying process has not changed. encodes the physics, the parameters of the experiment. This allows us to focus on two-particle scattering and set even if the real beams may contain as many as particles (the beam intensity of the LHC beams).

For a process of momenta , we have from (231)

| (233) |

Keep in mind that the volume here is the spacetime volume of the scattering, i.e. . For a single scattering, the probability is the number of scattered particles. Therefore the cross section

| (234) |

Identifying as the velocity of the beam relative to our cloud of particles , we can now write

| (235) |

We now need to convince ourselves that is Lorentz invariant since we could otherwise stop a process from happening simply by moving relative to it. We have already seen that the measure is invariant, making the entire phase space Lorentz invariant. The matrix element is also fine so that the remaining part is the flux factor . We an rewrite this in terms of invariants77 7 Note that technically this is only invariant for boosts along the beam axis. For boosts along any other axis, it is not invariant which fits well with our intuition of cross-sectional areas.

| (236) |

Example numbers from the LHC

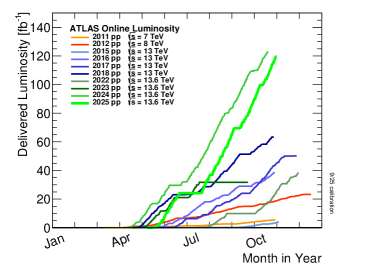

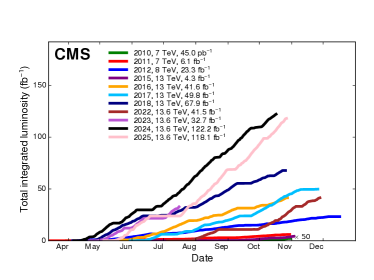

When talking about luminosity, we either refer to the instantaneous luminosity which is measured in or the integrated luminosity which is measured in . An instantaneous luminosity of for an entire year corresponds to .

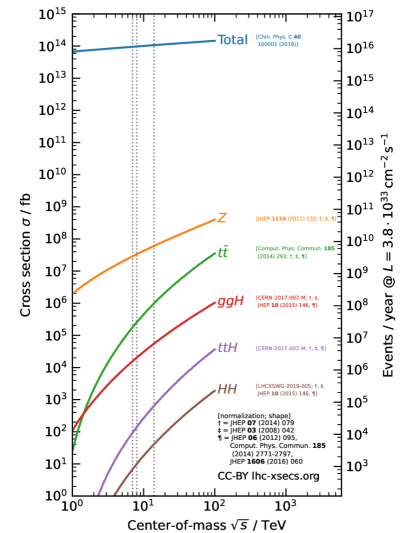

In 2024, the integrated luminosity of the LHC was around . The LHC experiments regularly publish plots that show the luminosity recorded as a function of time over the year. The current version is reproduced in Figure 5. At the time of the Higgs discovery (summer 2012), we had only recorded about , slightly more than recorded in any given month. You can use the numbers for various cross sections (e.g. or ) to find the number of events expected per year. cf. Figure 5.

4.2 One initial state: decay rates

If we have only one particle in the initial state, the only interesting thing that can happen is that this particle decays. We may wonder what the lifetime of this particle is or, if it has multiple possible decay channels, what the relative probabilities between the channels is. To do this, we define the decay rate which will be larger for shorter-lived particles (i.e. those with a larger transition probability)

| (237) |

where we have used that in the rest frame of the energy

4.3 Examples

Let us consider a few example of this. We will use a modified version of the theory we discussed in the previous section that contains two fields and

| (238) |

The Feynman rules of this theory are

| For each -- vertex | (239) | ||||

| For each internal line | (240) | ||||

| For each internal line | (241) |

We could have derived the Feynman rules using the Wick theorem as we did above. Alternatively, we could follow the heuristic of taking a prefactor of , multiplying the coefficient of the fields () and multiply with the symmetry factor ( for the factor and for the factor).

4.3.1 Decay process

If we assume that , the particle can decay into two particles. To do this, let us begin by calculating the matrix element which is trivial in this case

| (242) |

The decay rate therefore is

| (243) | ||||

| (244) |

As always we have and since , we have . We can now write the integration in spherical coordinates, i.e.

| (245) |

Since there is no angular dependence, we can solve the integral and obtain . To solve the integration, we can perform a substitution

| (246) |

We can identify as the velocity of one of the particles since it is defined as

| (247) |

with .

Suggested Exercise

Can you explain why we required based on this answer? What happens to for , for or for ?

The region is referred to as the threshold where the decay is just about possible and the two final-state particles are produced at rest.

Suggested Exercise

The decay is also possible. How would you go about calculating this? The first Feynman diagram would be

| (248) |

There are more diagrams due to the permutations of the outgoing particles. Convince yourself of the above and calculate the full amplitude.

More generally, it is useful to keep

| (249) |

in mind. Here and the integral was trivial.

4.3.2 Scattering of

Let us now calculate the scattering of two particles. The amplitude contains three diagrams

| (250) | ||||

| (251) |

Here we have defined the Mandelstam variables

| (252) |

Suggested Exercise

Use momentum conservation to show that .

The Lorentz-invariant phase space is calculated the same way as before

| (253) |

with . Unfortunately we now cannot replace because we still have an angular dependency. To see why, let us write down explicit four vectors in the centre-of-mass frame where . For simplicity, we align our coordinate system such that the beam axis is the direction and that the scattering takes place in the - plane

| (254) | |||||||

| (255) | |||||||

| (256) | |||||||

| (257) |

Since . For the same reason, and . The Mandelstam variables are

| (258a) | ||||

| (258b) | ||||

| (258c) | ||||

We can now write the differential cross section as

| (259) | ||||

| (260) |

If we set , we find a very short expression

| (261) |

What do we now do with this object? We can either visualise the differential distribution , normally written as or . Alternatively, we could integrate over and obtain the full cross section of this process occurring.

A few comments are in-order. From (258) it is clear that and . This means the second and third term in (259) will not be a problem as long . However, is allowed and the cross section would explode if we picked this value of . This is fixed by adding higher-order corrections to the propagator, i.e.

| (262) |

Even though each term is progressively more suppressed by , the addition of more propagators makes up for this and we need to calculate infinitely many such insertions. We will come back to this in Section 7 and Appendix A.

We should also note the behaviour of (261) for . This corresponds to a scattering angle of or , i.e. when the outgoing particles follow the beam axis. Since the two particles are indistinguishable, this just means that the particles pass each other without interacting. The divergence we see here is to the fact that we have split the matrix as in (227). When we constructed we assumed that the initial and final state were different which is not the case for .